Accepting My Autistic Self: Why I’m Done Trying to Fit In

“I care for myself. The more solitary, the more friendless, the more unsustained I am, the more I will respect myself.” ~Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre

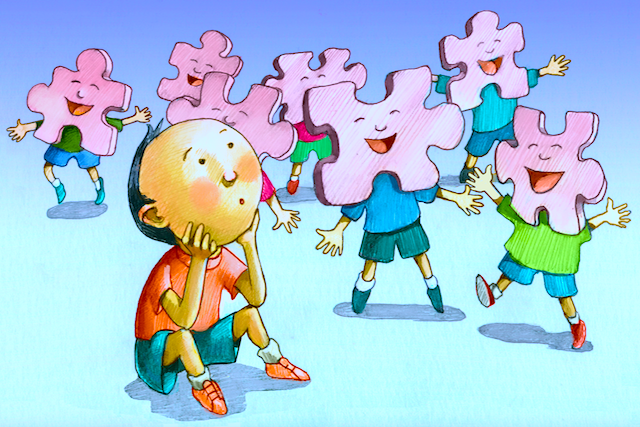

A common misconception about autistic people is that we don’t care if we’re alone. Of course this varies with each person, but on the whole, it’s untrue. We want to feel included, it’s just not easy for us to fit in. There are other days when I feel autism has separated me so fully from other people that I am functioning on a different plane of existence, not just with a different brain structure.

I attended a child’s birthday party recently, and it was a sensory nightmare. Children screaming, rain pouring, karaoke, a pinata, one incredibly friendly, one-ish looking, adorable baby boy who used me as a jungle gym. Before all of this was simultaneously happening, my family had arrived a few minutes early to secure a good parking spot.

The five of us unloaded from our van and went inside. There was mostly family there, no one unknown yet, only a half dozen people, still pretty quiet and cozy. My sister-in-laws were doing rounds with the multiple sets of in-laws and close friends everyone knows.

Recently diagnosed, I’ve been making more of an effort to put aside my discomforts and reach out in different ways to form stronger family bonds for my children. I usually retreat to my phone during children’s parties that are not my own children’s, but this time I attempted to mimic my sisters-in-law. I put my purse away and went in turns attempting to make conversation with my family.

The same experience happened with five different people. They would say something and I would reply with something in return. After each time I spoke it was as if I’d said nothing; they would speak after my comments as if I had interrupted them, despite me answering direct questions or comments.

I gave up on conversation when things started getting busy, and switched to attempting to give my niece the blanket I’d been crocheting for eighteen months. My niece is only almost one, so I gave it to her mom to open. She did not take it from my outstretched hand, nor did she show interest in it while I was there.

When all our kids were settled in the car and my husband was driving home, it began. Anxiety, guilt, self-doubt. What do I do wrong? Why can I not think of things to say that spurn conversation? I’ve spent a large amount of time trying to understand facial expressions I was not built to read. Did I not read them well? And how could I still be failing at talking about the weather?

I asked my husband, what am I doing so wrong? I did all the same things that my neurotypical sisters-in-law did. Why did they not chat with me for fifteen minutes like they all did with everyone else? I showed interest in their lives, taking care to avoid my special interests.

I stewed over it, I cried and called myself a failure because I can’t seem to connect with people and can’t pass for normal, even though I now know why, after thirty years.

I was crushed that knowing why I was different made no impact when it came to bridging the difference. As I continued to think about this I eventually concluded that not knowing my diagnosis, or if I even had one, gave no one an excuse to treat me poorly.

Then I realized there was nothing wrong with how I attempted to connect. The problem wasn’t me; it was the people I was trying to interact with. I asked myself, who and what was I failing? People who wouldn’t even talk to me.

I then remembered that I get to choose how I react. I get to choose to feel bad or move on, and I needed to ask myself what I wanted to feel—and what I deserved to feel. So I decided right then I don’t want to be affected by people who simply don’t care for me.

I will probably never connect with my sister-in-laws, not one of the four. I’ve put in a lot of effort trying and failing. The way I choose to see it now, I was born with the ability to weed out shallow relationships.

I didn’t do anything wrong besides not be my true self. The traits I was born with should not determine other people’s treatment of me, just as my treatment of others is not dependant on them, just myself.

I will never pass for your typical wife or mother. I didn’t for the first thirty years of my life when I didn’t know I was autistic. I doubt I will in the next thirty years with an explanation for my traits and behavior. I am learning that is not just okay, but great.

I choose now to live like it’s not my job to sacrifice my comfort because I socialize differently. I don’t owe anyone “normalcy.” I don’t need to try to mask my autism by copying a seemingly normal routine. By attempting this I stole the joy out of my own experience. I felt anxious and frustrated and ultimately like a failure.

I still crave company, but good company will come on its own. They won’t expect me to fake anything, mimic anyone, or wonder or ask why I seem different. They will just be with me and accept me as I am.

Being autistic has impacted my entire life, and for most of my life I never understood what was happening. I got blessed with an extra set of challenges I had no choice over. But I do get to choose how strong those challenges make me.

I choose to get stronger every day. I choose to be my own hero. Every day, I choose to let go of my self-doubt and hold on to my true self.

![]()

About Shyanne Stillwell

Shyanne is a mother, birth mother, wife, author, and animal enthusiast. She has been reading and writing her entire life and was published first in a poetry book at age twelve and again at twenty-five. Diagnosed late in life with autism, she has devoted her time to helping people understand and accept autism without trying to change it.

Comments